Philadelphia City Hall, looking towards a bright future?

With the mask mandate coming back and another wave of Covid possible, the possibility of moving on from the pandemic is dimmer than it seemed a few weeks ago. Still, we all would like a future of never hearing about variants again – but what does that really mean to move into a post-pandemic future?

The Pew Charitable Trusts’s Philadelphia Research and Policy Initiative recently released a report comparing Philadelphia’s current economic situation with pre-pandemic times, saying, “Philadelphia’s economic trends were the strongest in its recent history” in the period leading up to the pandemic. But as all too many Philadelphians know, things were not good back in those hazy, pre-pandemic times of normality, and we cannot afford to go back there if we want a better future.

Even before COVID-19, Philadelphia’s “normal” did not serve the interest of everyday Philadelphians. A return to our pre-pandemic ‘normal’ would mean the city government continuing to help powerful corporate interests to dodge taxes and rip off workers, favoring plutocrats from the Chamber of Commerce and real estate developers. Instead, we should aim to envision a different kind of future: one that breaks from our past of poverty, gentrification, police violence and racism, and builds a city where we can all live and thrive with great public services and equitable resources.

Economic Growth, but only for some

It’s true that Philadelphia’s economy grew in the years preceding the pandemic, going from 657,400 jobs in 2010 to 740,600 in 2019 and the city’s GDP rising by about $18 billion (adjusted for inflation from the report’s Table 1). However, that does not mean that living conditions for all Philadelphians improved dramatically. As the report notes, “The largest growth came in sectors requiring higher levels of education and training, and many of those jobs were filled by commuters. For city residents, increased employment was concentrated in low-wage sectors, widening the pre-existing disparity between resident and nonresident wages.”

For city residents most of the new jobs available were in sectors like Retail, which had a median income of a mere $25,800, and Leisure and Hospitality, which pays a below-starvation median income of $21,100. These salaries are appalling in a city where the average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment ranges from $1,400–$1,800 a month. With poverty wages and rising costs of living, the pre-pandemic ‘normal’ meant that workers in those low-wage industries struggled to get by while their employers reaped profits.

The report details that, along with job growth, the poverty level in Philly dropped from 2010-2019, though the city was still the poorest big city in the country. However, the report does not specify whether that drop was a result of improved conditions for low income Philadelphians, or from wealthier residents moving into the city and gentrification pushing others outside of the city limits.

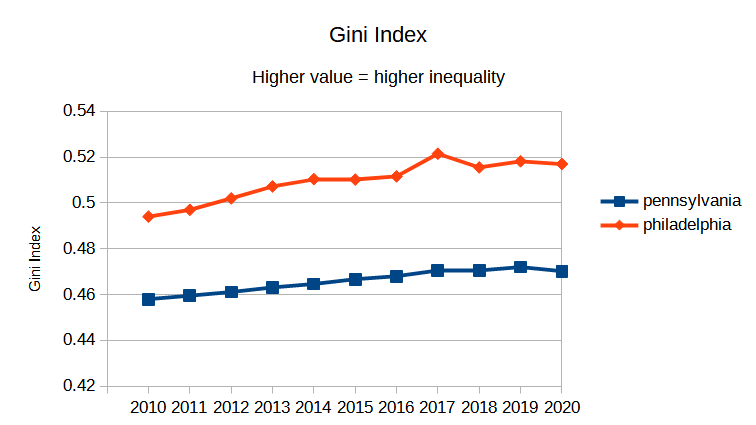

Source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey

Recent data suggests that drop may be linked to the latter, with wealthy residents pushing lower-income residents out. According to the most recent report from the American Community Survey of the Census, economic inequality grew in Philadelphia from 2010-2020 at a faster rate than other cities, and Philadelphia was the most unequal county in PA. Home ownership also declined in Philadelphia to below 50% as did the rate of rental vacancies, indicating rising rents.

Despite the report’s tale of ‘economic growth’ (underpinned by a real estate tax abatement and regular cuts to business and wage taxes), the old way of running things resulted in a more inequitable and unaffordable city.

A Return to… Failed Policies?

The Pew report itself does not suggest how to improve the inequities and make the city more affordable. Instead, a related report on 4 scenarios of future growth says that the city should “bolster..competitiveness/attractiveness” to “produce a greater return”. While this statement may seem neutral, it relies on a breadth of underlying conservative and neoliberal assumptions that favor corporations and wealthy developers.

A closer look at the research underpinning this series of Pew reports explains its recommendation towards increasing business competition. The research was done by an outfit called Econsult Solutions, Inc, a local consulting firm that specializes in urban economic research and is widely used by businesses, institutions, and the government. While they have a long client list, there’s reason to be wary of Econsult: their previous reports have promoted development projects that help wealthy corporations dodge taxes but have been demonstrated, through time and research, to provide very little benefit to anyone other than the large corporations and real estate developers that pay them.

So how does Econsult define ‘competitiveness/attractiveness’? Unsurprisingly, when they list the factors that influence competitiveness, the first one is “tax rates and the mix of taxes imposed upon businesses and individuals.” While they do mention affordable housing and infrastructure, they emphasize the power of taxes in terms of, “encouraging business creation and expansion.”

Over and over, groups like Econsult claim that cutting business taxes and giving tax credits will create jobs (usually without mention of whether those jobs can actually support people’s lives. And over and over, these trickle-down economic policies have failed to solve issues of inequity.

For example, the city’s recent Job Creation Tax Credit program only created 21% of the jobs promised from 2002-2019. While we do need more good jobs in the city, we need to be sure that our policies don’t just return our city to the pre-pandemic period of ‘growth’ that perpetuated inequalities. We need to focus on new solutions instead of the same tired, and failed, policies that did not bring real prosperity to all before the pandemic.

Creating a New Future Beyond ‘Normal’

If cutting taxes and increasing ‘competition’ is ineffective, how do we create a future where Philadelphians can really thrive? We need to prioritize creating jobs that pay living wages and allow workers to have a say in their workplaces through unions and cooperatives. We need to fully fund our public education system, including k-12 and the Community College of Philadelphia, and enact and enforce policies to support and protect affordable housing.

Good jobs, strong public education, affordable housing, and more are possible and can be done with public resources. The employment sector with the highest wages ($64,400), and large representation of city residents (68%), black workers (45%), and those without a college degree (72%) was not in the world of private business, but the public sector. There isn’t a single, simple solution to our situation, and inequities remain in pay and racial equity for public workers that need to be addressed by raising wages and addressing discriminatory hiring practices. But if we want to create an equitable city we cannot return to policies that didn’t work in a time of supposed economic growth. Instead we need to examine what was wrong with our policies over the past several decades, who profited during a pandemic that wreaked havoc on the most vulnerable of our neighbors, how to create the kind of city that supports all of its residents, and what kind of policies can create a better future.

Over the next few weeks, we will explore these issues through a series of articles, including what happened during the pandemic, the recent economic policy history of Philadelphia, and how we can create a more just and equitable city. Check out our resources, sign our petition, follow us on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook, email us, and keep checking this space for more articles!