For decades, the City of Philadelphia has repeatedly cut taxes for corporations, real estate developers, and the rich. As a result, vital public services are starved of resources. Libraries are closed on weekends, trash pick-up schedules are delayed, sidewalks and streets are crumbling and full of potholes, many of our schools and rec centers have fallen into disrepair, and programs that could improve community safety, like mobile crisis teams, are underfunded.

Despite promises that tax cuts will trickle down and support local job growth, instead, poverty and inequality rates in Philadelphia have remained stubbornly high or have risen. Yet each year, you can count on certain members of City Council like Allan Domb, supported by the Chamber of Commerce and real estate industry groups, to call for further tax cuts. This year we could choose a different path—instead of cutting tax rates, we should prioritize tax relief for tenants and lower income homeowners and create a wealth tax to help ensure that the rich pay their fair share.

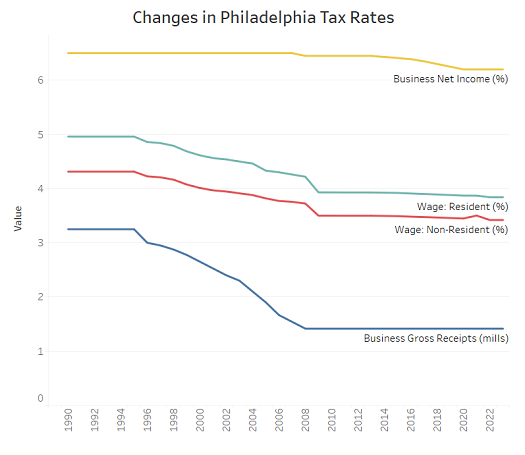

Philly taxes have already been cut substantially over the past three decades. Tax rates for the three largest sources of City revenue (wage/earnings tax, real estate property tax, and business income and receipts tax, aka BIRT) have all been decreasing. The business gross receipts tax (part of BIRT) is less than half of what it was three decades ago, and wage tax rates have decreased by over 20% since the early 1990s.

The real estate property tax rate today is 1.3998%. In FY13, this tax rate was effectively 3.127% of the “certified market value” of properties, more than twice as high. During the Actual Value Initiative in 2013, when reassessments and changes to the assessment process caused many assessed property values to rise substantially, the City chose to dramatically cut the property tax rate to 1.34% in FY14, offsetting all of the potential increase in property tax revenue that reassessments could have generated.

From 1913 until 1997, Philadelphia had a personal property tax on holdings of stocks and bonds, similar to the wealth tax that would be created by a bill recently introduced by Councilmember Kendra Brooks. The Philly personal property tax was eliminated after billionaire Walter Annenberg challenged the legality of the prior version of the tax at the PA state level, causing suburban counties to get rid of their personal property taxes. Banks like First Union, PNC, and Mellon then held the City of Philadelphia hostage by moving jobs and assets to the suburbs and saying they would only return if the tax was eliminated.

Beyond these broad tax cuts, the City has created major tax waiver programs that benefit wealthy developers and large corporations, like the 10-year property tax abatement for new development and renovations in 2000 (expanded from a more limited version of the abatement that was introduced in 1997). The City has also continually approved new Keystone Opportunity Zones since the program’s start in 1998, despite a highly questionable record of these zones actually creating the amount of jobs promised. A 2014 analysis found that for each new job created by a Keystone Opportunity Zone, the City lost more than $100,000 in tax revenue.

Whenever there is a chance to bring a new major corporation to Philadelphia, the City rolls out the red carpet with enormous tax breaks and incentives. For example, the City and state offered $1 billion in tax breaks in their failed attempt to bring Amazon’s second headquarters to the city in 2018, the same year Amazon counted over $232 billion in revenue and $30 billion in profits.

Corporate-friendly consultants tell us that we have to cut taxes in order to attract development and businesses to our city, but at the same time many other municipalities are doing the same. The end result is a race to the bottom with cities competing to see who is willing to gut their public services the most in order to appease profit-hungry corporations.

In reality, underfunded education, sanitation, public transit, libraries, rec centers, and other public services; high costs of housing; and lack of community safety are doing much more to push people out of Philadelphia than tax rates. Underfunded schools do not provide the same opportunities as those found in wealthier districts to develop the skills demanded by employers in the 21st century. At the same time, the companies which the City bends over backwards to entice tend to hire suburban commuters, not city residents, for high-paying jobs, doing little to improve the lives of Philadelphians.

Nevertheless, some of our elected officials continue to be convinced by the trickle-down economic logic that tax cuts will boost the economy more than increasing investment in public services. By supporting these tax cuts, they are prioritizing the demands of corporate and real estate lobbyists over those of working class Philadelphians who want well-functioning public services.

In 2021, the Chamber of Commerce for Greater Philadelphia spent thousands of dollars on ads supporting tax cuts. The Chamber also donated $30,500 to Philly elected officials and spent $15,000 on lobbying in 2021. The executive committee of the Philly Chamber of Commerce board includes executives from Comcast; PECO; Fulton, Citizens and PNC Banks; University of Pennsylvania; water privatizer Essential Utilities; pharmaceuticals company AmerisourceBergen; and venture capitalist/Inquirer Chairman Josh Kopelman. The Chamber recently launched a new group called the “Inclusive Growth Coalition” which argues that “pro-growth” policies like tax cuts will generate more city tax revenue by expanding the tax base, even though studies of proposed BIRT tax cuts have shown this is not the case.

The real estate sector is one of the largest sources of political campaign funds for current Philly elected officials. Lobbying groups like the Greater Philadelphia Association of Realtors work in close collaboration with some members of City Council to help craft legislation that supports their interests, such as bills to dramatically cut and/or eliminate portions of the BIRT tax and keep the 10-year property tax abatement intact. The real estate sector is disproportionately affected by the City’s business net income tax, which City Councilmember Allan Domb (who owns a major real estate company himself) has called to eliminate. About 18% of net income tax revenue comes from the real estate sector, while only about 7% of gross receipts tax revenue comes from this sector.

https://public.tableau.com/shared/PN6RDJXB8?:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link

After failing to push through most of their initially proposed tax cuts in 2021, Mayor Kenney and some members of City Council created a Tax Reform Working Group “to study and recommend changes to the city’s tax code to support Philadelphia’s equitable and inclusive recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.” The group consisted of appointees—several of whom have decidedly anti-tax perspectives—with no representatives of public sector unions, progressive advocacy groups, or community-based organizations. In October 2021, with little advance notice, the group ran an online survey for a couple of weeks, as their method of gathering public input. After several months of meetings, as far as we can tell, the working group hasn’t actually produced any public recommendations or released the results from their survey. But we expect that corporate-friendly politicians will continue to point to the work of groups like this, with unrepresentative compositions and little opportunity for public input, to justify future proposed tax cuts.

Heading into the 2023 mayoral and City Council elections, we also expect to see several political action committees (PACs) funded by corporations, developers, and billionaires spend large amounts of money supporting candidates who will support an agenda of more tax cuts for big business and real estate.

Mayor Kenney often points to the PA uniformity clause as what prevents Philadelphia from creating more progressive tax policies. While he is right that the uniformity clause is a major obstacle which the Republican-controlled PA state legislature is unlikely to change anytime soon, this should not prevent the City of Philadelphia from exploring options for shifting the burden of local taxes toward the rich. The wealth tax proposed by Councilmember Kendra Brooks would be a step in the right direction. This year’s large increase in property tax assessments also offers an opportunity to increase tax revenue from wealthy real estate owners, but it is crucial that the City follows through with tax relief measures for lower income homeowners and tenants who will be negatively affected.

We can choose to turn the tide of tax cuts and austerity. By taxing the rich, we can ensure that public services are fully funded and build a well-functioning, safe, just, and flourishing city.